India celebrated 75 years of Independence from the British on 15th August, 2022. That’s a huge milestone. India’s economy has undergone some major changes since then. In 1947, India’s GDP stood at ₹2.7 lakh crore. Now, it’s close to ₹150 lakh crore! Despite all the bumps, we sure have come a long way. Let’s look at some of the changes that have resulted in the economy as it is today.

During independence India was an agro-based economy with a whopping 75% of the Indian population engaged in agriculture. Basically, on the eve of independence, the Indian economy was characterised by lack of economic development. It was developed only to cater to the needs of the British government. Railways, ports, post and telegraphs were developed to promote the process of colonial exploitation of the Indian economy. All the changes introduced were towards the protection and promotion of the economic interest of the British economy, rather than the Indian economy.

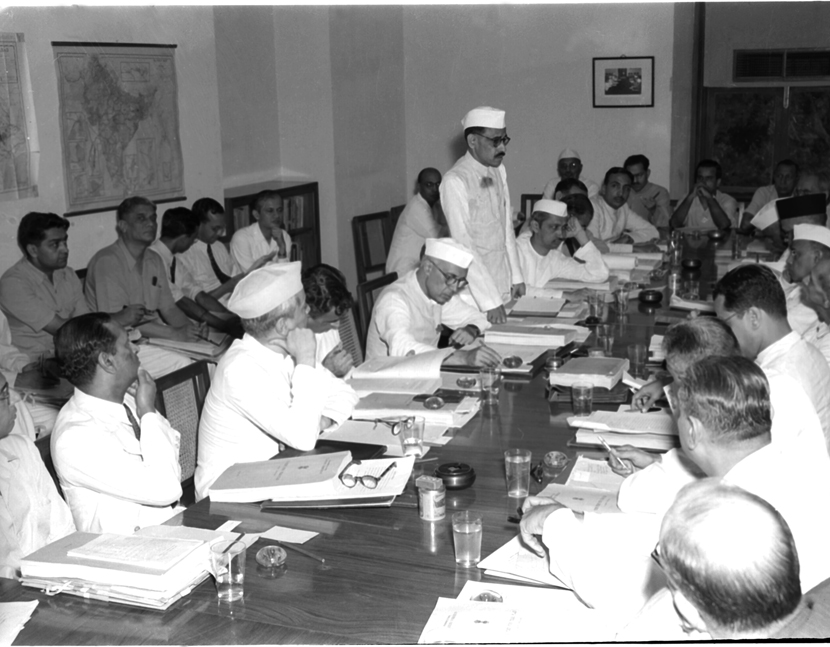

After things settled down in the country after partition, the leaders saw that the economy that they had inherited from the British was backward as the level of output and productivity were low. They realised the need for economic planning. Thus, the planning commission was set up in the 1950 under the chairmanship of the then Prime Minister Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru [it was eventually dissolved and replaced by the NITI Aayog in 2015]. To ensure that planning covers both spheres of activity, economic and social, India adopted the model of ‘Five Year Plans’ in 1951. All the five year plans had certain common goals such as: GDP growth, modernisation, self-reliance and self-sufficiency, equitable distribution etc. The last of these plans was introduced in 2012. These plans documented not only the specific objectives t be achieved in the five years of the plan, but also what is to be achieved in the long run. This turned out to be quite helpful, particularly in achieving specific goals.

There is a general trend wherein developing countries experience a shift in employment from the primary sector to the industrial or secondary sector. Wanting a similar change in the Indian scenario, the Industrial Policy Resolution (IPR) was adopted in 1956. It was a comprehensive statement to facilitate industrial development across the country. This resolution laid a roadmap of the Second Five Year plan. The principal elements of IPR, 1956 are:

1. Classification of Industries into three categories on the basis of ownership:

– Those which would be established exclusively as public sector enterprises.

– Those which would be established as both, public and private, sector enterprises.

– All industries other than those in the above categories were left to the private sector.

2. Industries in the private sector could be established only through license from the government. The main focus was to promote social welfare rather than private profits by liberally issuing license for the backward regions rather than the developed regions of the country.

3. Private entrepreneurs were offered many types of industrial concessions for establishing industry in the backward areas of the country like tax holiday and subsidised power supply. This was expected to promote regional equality.

Around the same time, Indian farmers were looking for a way to tackle low productivity. Most farmers were dependent on rainfall for the success of their crops and continued to use outdated technology. To solve their problem, they were introduced to HYV (High Yielding Variety) seeds. Use of HYV seeds along with chemical fertilisers, insecticides and pesticides led to substantial rise in the level of agricultural input. The rise in output was so significant that it was called the ‘Green Revolution.’ It took place in two phases: Mid-60s to Mid-70s and Mid-70s to Mid-80s. Other than a spurt in crop productivity, the green revolution resulted in an increase in the area under cultivation and induced a change from substantial farming to commercial farming. It changed the farmers’ outlook and helped India achieve self-sufficiency in food grain production. It is because of those changes that today India is able to meet its own requirement and export wheat to countries in need. However, the revolution had its shortcomings. The revolutionary rise in output was confined mainly to the production of food grains. No similar rise was seen in the output of pulses and commercial crops like jute, cotton, tea etc. The effects of the revolution weren’t uniform across the country. In states like Punjab, Haryana, West UP, Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu etc. it made a remarkable impact. Whereas, in states like Madhya Pradesh and Odisha, its impact was relatively insignificant. Since a bulk of the Indian farming population consists of small and marginal farmers, they were not able to reap the benefits of the revolution due to high cost of HYV technology. It also widened the gulf between the rich and poor farmers. However, despite the shortcomings, it impacted many farmers across the country.

During this period, India also adopted the strategy of import substitution. This implies self-sufficiency in those goods which the economy has been importing from the rest of the world. It’s a strategy to save foreign exchange by restricting the volume of import. Foreign exchange was mostly just utilised for developmental imports during this time. It also protected the domestic industry from foreign competition. This was considered important as Indian industries were still being set-up.

All of these changes were introduced between 1950 and 1990. As a result, the proportion of industrial sector in GDP increased from 13% to 24.6%! The industrial output recorded about 6% annual increase in output during this period. The then sunrise industry (electronics in particular) marked its emergence in the domestic economy. This was complemented by the growth of large-scale industries (like Rourkela and Bhilai Steel Plants). Briefly, there was a structural shift in the economy as the significance of the agricultural (in terms of contribution to GDP) started declining in favour of the industrial sector. It seemed like everything was going according to plan.

Despite all these changes and reduced dependence on agriculture, almost 65% of the population continued to be employed in the agricultural sector. This implied that growth in the industrial and service sector was not sufficient to absorb the surplus labour force of the agricultural sector. Consequently, the planners were faced with a situation of massive rural employment in the economy, besides growing unemployment among the educated youth in the urban areas. Furthermore, the excessive regulation and protection from foreign competition led to lack of competitiveness and inefficiency of the domestic producers. With the passage of time, the bad effects of these strategies overshadowed the good effects. The planners had to come up with a solution.

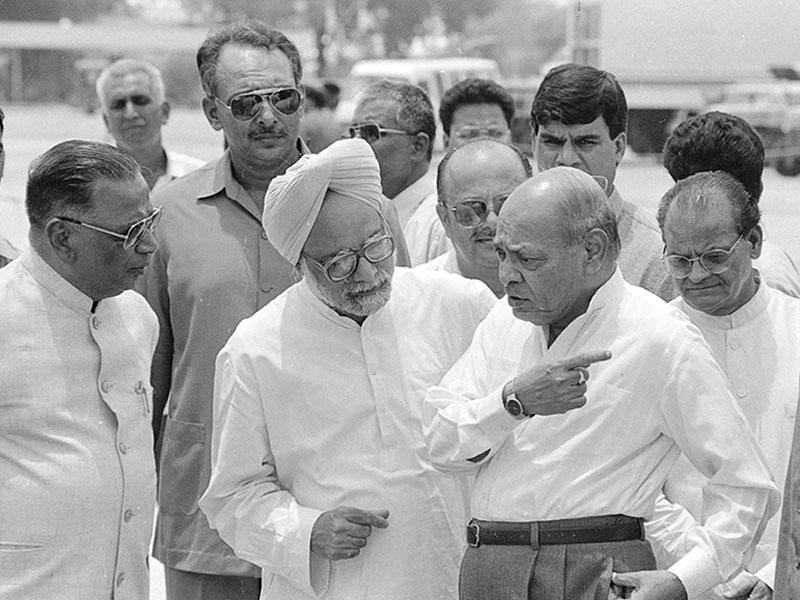

Before they were able to solve that problem, they were faced with another, much bigger problem- the forex crisis of India. India had a ballooning fiscal deficit by 1990-91. The balance of payments situation had deteriorated sharply. By March of 1991, the country’s foreign debt was about $72 billion and its forex reserves had dropped to $5.8 billion. These reserves barely covered two weeks worth of imports. This was also a period of political instability, with three governments in three years led by V.P. Singh, Chandra Shekhar and finally Narsimha Rao.

The problem required intervention beyond the RBI and the government. The government under Chandra Shekhar took the advice of the RBI and pledged their gold reserves, in hopes of helping with the crisis. This was followed by a complex and confidential operation whereby nearly 47 tonnes of gold was shipped off to destinations abroad. This helped raise about $400 million for the government. By this time a new government, under the leadership of Narsimha Rao, came to power. Even though the decision to pledge the gold had been taken by his predecessor, Rao and his new finance minister Manmohan Singh backed it to the hilt.

They also managed to secure a loan from the World Bank and IMF (International Monetary Fund) worth US$ 7 billion, on the condition that the Indian economy would be opened up to foreign investors by removing quantitative restrictions and liberalised to ensure increased participation of the private sector in the process of economic growth. It also required that the participation of the government sector would be reduced in areas where it had established monopoly. India didn’t have much of a choice but to agree to these conditions. As a result of this deal, the new economic policy was launched in the beginning of 1991.

The three main components of this policy are: Liberalisation, Privatisation and Globalisation. These changes meant that the economy was free from the direct or physical controls of the government. There was no license required, the number of industries reserved for the public sector was reduced, industries were provided freedom to import capital goods etc. India switched to managed floating rate system to determine the exchange rate of the Indian rupee and allowed Foreign Institutional Investors (FII) to invest in Indian financial markets. The government reduced their role in the economy and sold off some of their public sector enterprises. Private sector was given more responsibility as the public sector gradually withdrew their ownership/management. And lastly, the Indian economy was integrated with the economies of other countries under conditions of free flow of trade and capital across borders. It linked the Indian economy with the global economy.

The new economic policy, 1991 was a defining moment for the Indian economy. It responded to the changes with a surge in growth, which averaged 6.3% annually in the 1990s and early 2000s, a rate double that of earlier times. Thanks to this, India had reached a comfortable level of foreign reserves. The fiscal deficit was bought down from as high as 8.5% of the GDP to around 3.5% of the GDP. There was an influx of private foreign investment which helped the domestic industries grow and led to the introduction of new technology. Owing to these policies, India opened up its economy for the rest of the world and was finally recognised as an emerging economic power.

On the eve of the reforms, the public telecom monopoly had installed five million landlines in the entire country and there was a seven-year waiting list to get a new line. In 2004, private cellular companies were signing new costumers at a rate of five million per month. The number of people who lived below the poverty line as a percentage of the total population declined more rapidly than at any other time since independence.

The sectors that have experienced the most growth are services and capital-intensive manufacturing. IT and pharmaceuticals are the two sectors of the economy with international renown. The IT industry grew faster than anyone expected and their growth wasn’t limited to the Indian market. Although the Indian domestic IT market is large and growing, production for exports is growing faster than production for the domestic market. As a result, the share of exports in total IT output has risen from 19% in 1991-92 to 49% in 2000-01 to 81% in 2014-15. Many large companies like Infosys and Wipro established their presence in international markets and gained worldwide recognition during this time.

However, the 1991 reforms wasn’t a magic solution that made all the problems disappear. Majority of the labour force was engaged in a low-productive sector consisting of agriculture and urban informal jobs. We had abundant labour and not enough jobs for them. Many MNCs found India a good location to set up their business due to cheap labour prices as compared to many other countries. The government saw this as an opportunity and introduced SEZs (special economic zones) and labour law flexibility to foreign companies who wished to set-up production in the country. India also became a hub for outsourcing. Due to cheap and excess labour, business started to consolidate contact and service centres in the nation. The sector has also diversified beyond its beginnings as little more than IT and call centres; outsourcing now offers almost every service imaginable. BPO in India, for example, has a strong reputation in ITES (Information Technology Enabled Services) outsourcing, with qualified staff able to work remotely in areas like coding and support.

Two of the most talked about economic events in the 21st century are demoetisation and Goods and Services tax (GST). On November 8, 2016, PM Modi suddenly announced that all ₹500 and ₹1000 value notes will become invalid by midnight. This move was to flush out the black money hidden from the taxman. This announcement led to 86% of the currency in circulation becoming invalid by midnight. Chaos ensued the next few weeks as people stood in long lines at the bank, waiting to get their old notes exchanged for new ones. However, as an outcome of this, digital payments were given a boost and paved the way for apps like Paytm and ultimately UPI payment. It integrated e-wallets into the economy.

Closely followed by this, GST was introduced. It had been in the talks for many years and finally launched all over India with effect from 1st July 2017. This made India one of the few countries to have an indirect tax law that unifies various central and state tax laws. The new system has removed tax barriers across states and created a single common market.

The next major event that took place was, well, the pandemic. It caused a slowdown in economic activity in the beginning, followed by a boom in tech businesses. We were in a stock market bubble and even loss making companies had stellar debuts on the stock market (think: Zomato). The bubble did burst eventually but it was nice while it lasted. We sort of faced an edible oil crisis. The Russia-Ukraine crisis caused further disruptions in supply and fuel. There is an ongoing chip shortage which still seems to have no way out. And recently, much like the rest of the world, we’re dealing with inflation! (Although, retail inflation eased slightly to 7.01% in June). If you scroll back, you’ll find a lot of stories on how the Indian economy was impacted by the virus.

Anyway, as you have read, it has been one hell of a ride for the economy since independence. India acquired a stagnant and backward economy from the British. Now, it’s one of the world’s fastest growing economies. India’s economy has shown tremendous progress but we still have a long way to go! I’ll be back for an update in 25 years 😀

Leave a comment